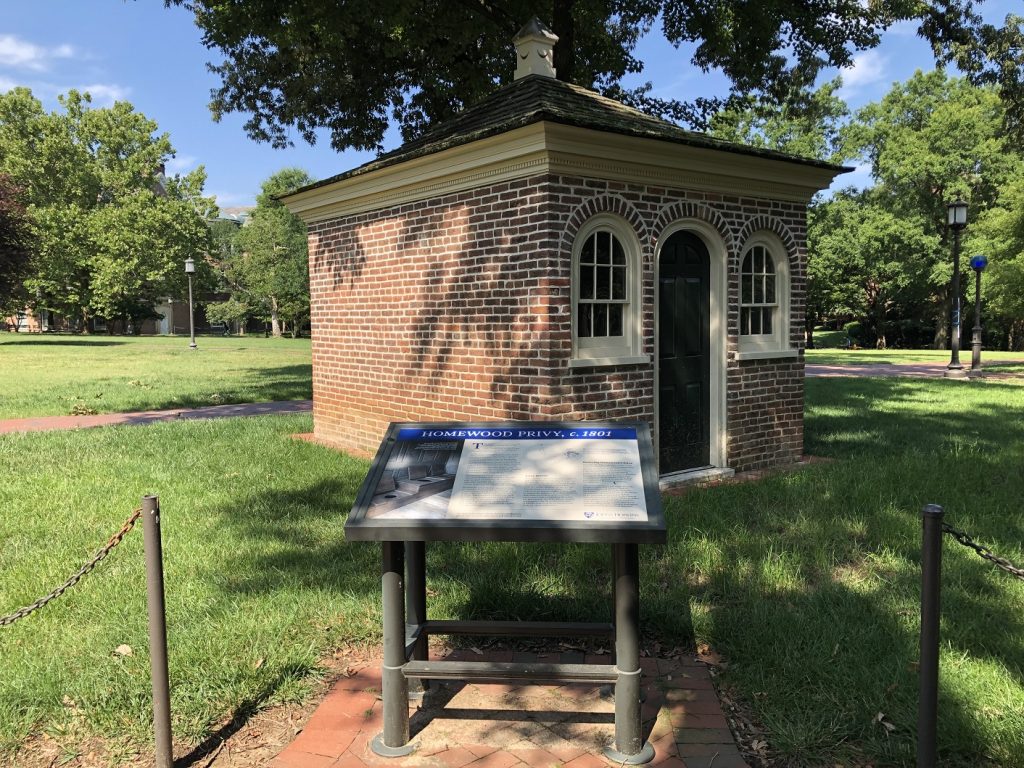

Throughout the summer and fall of 2022, carpenters, masons, and painters worked to restore the interior of Homewood Museum’s historic privy.

Built between 1801 and 1804, when construction on the main house was underway, the privy is a relatively intact structure with no additions or significant alterations made to it over the course of its long existence. As such, the renovations provided an opportunity to reexamine in detail the structure’s construction, styling, and historic use, yielding important insights into daily life at the Homewood estate during the early 1800s.

This privy is no ordinary outhouse. Unlike many outhouses of the time, which were constructed of lightweight materials for easy relocation, Homewood’s square, brick privy was sited with great care and built to last. Its lavishness speaks to a historical moment in booming Federal-era Baltimore: grand country housing with elegant amenities for residents and their guests.

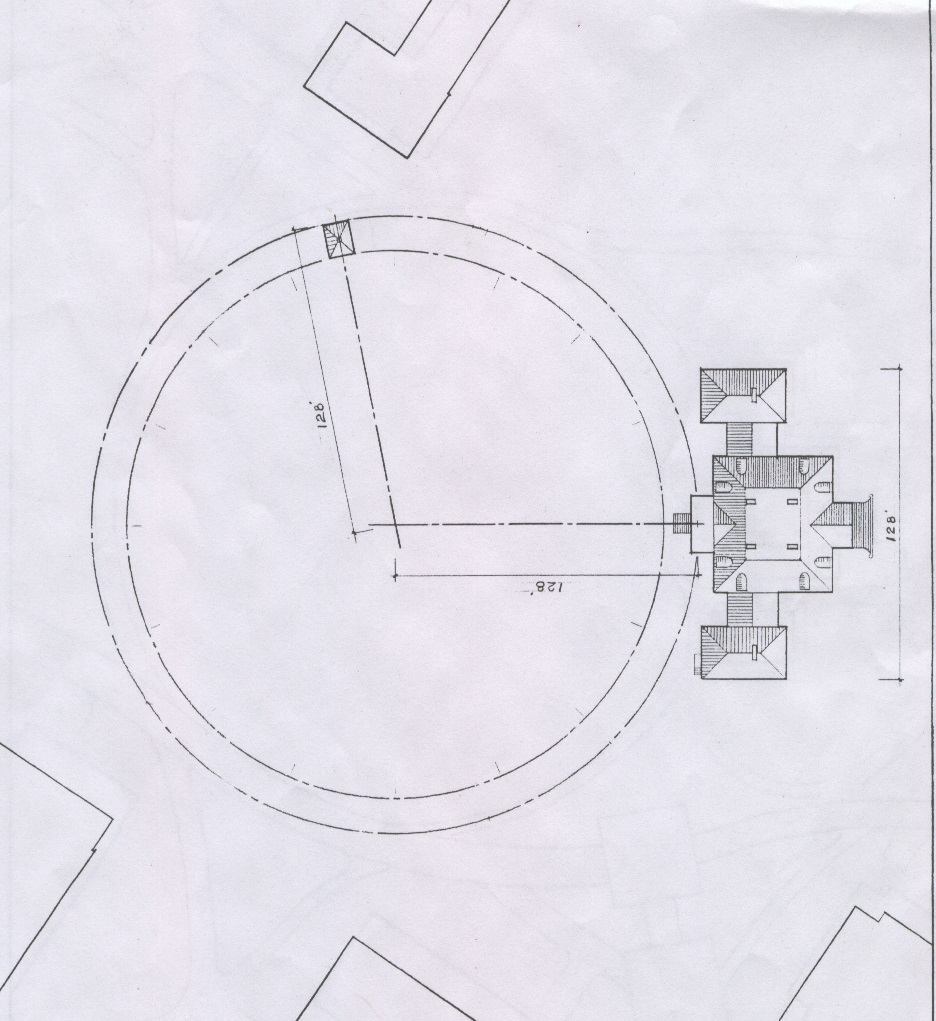

Marking the boundary between the gardens and the orchards, the privy was part of a sophisticated mathematical plan influenced by Renaissance architecture. The overall 128-foot length of the house was used as the radius of a circle whose center is 128 feet from the north porch. The privy falls on the circle’s circumference, becoming part of the villa’s overall design scheme. Roses and other fragrant plants nearby would have helped to control odors, in addition to regular cleaning of the stone-lined pits below the privy’s seats.

The privy itself is divided into two chambers, each accessed by a separate exterior door. Presumably, the west side, with its three seats, was for men, while the east side, with two adult seats and two smaller seats, was for women and children. Windows and a central vent stack provided ventilation, and the privy could be “sweetened” by the addition of lime.

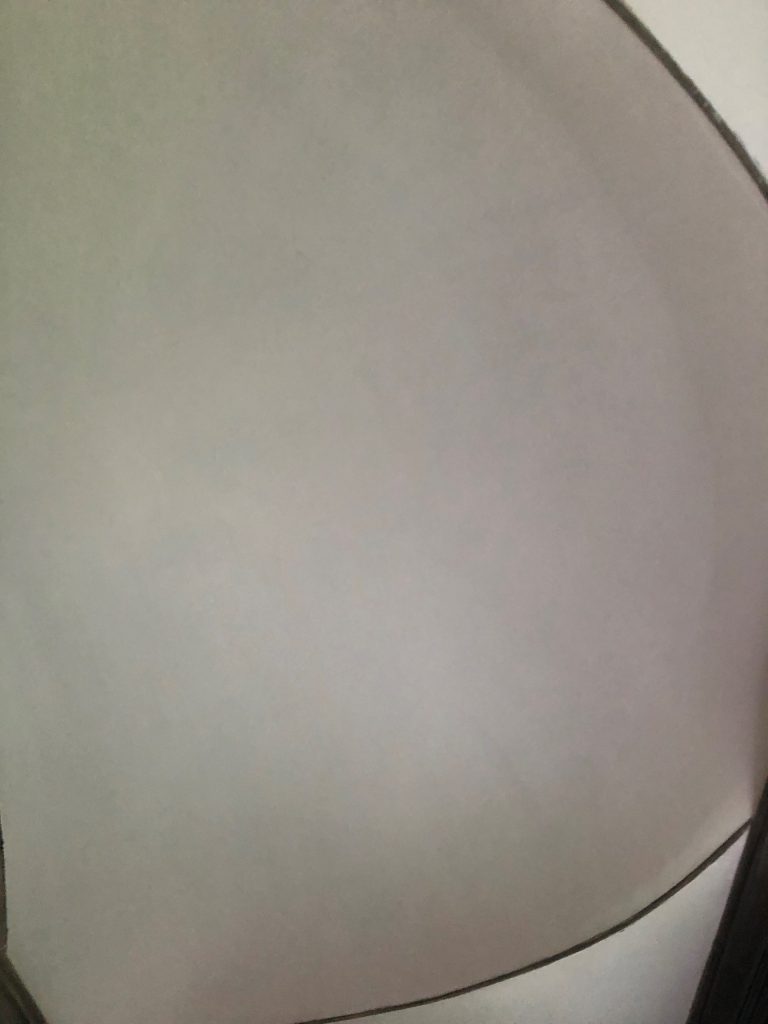

Notable interior elements include half-dome plastered ceilings with crown molding and wood-paneling painted to imitate stone, a nod to the paneling in the home’s main Drawing Room. Both sides of the privy still bear early-20th-century “graffiti” from when Homewood was the location of the Country School for Boys and the privy functioned as the boys’ lavatory.

Work to stabilize the interior of the privy was performed by carpenters, masons, and painters from the Delbert Adams Construction Group. Specific projects included: carpentry and millwork to fabricate wood lathing strips for replacing sections of the plaster ceiling, replacing ceiling framing, replacing flooring in the west-side chamber and replacing missing sections in east-side chamber, reinforcing the west-side subfloor, and repairs to damaged trim, including baseboards, crown molding, and window trim. Brick skirting also was added around the base of the Privy to prevent roof runoff from soaking the ground and damaging the foundation. Updated signage was fabricated and installed as well.

The renovations also sparked a re-examination of how use of the privy may have cut across lines of gender and status. Indeed, the number of holes in the privy suggests that using the privy was a group activity. But did only the Carrolls and their guests use the privy? Or did the enslaved women at Homewood, like Rebecca Ross and Charity Castle, facilitate its use for the Carroll children in their charge?

A lack of historical evidence makes it impossible to answer the question definitively. However, research conducted by Elizabeth Sheehan, a JHU undergraduate student who examined the history of mid-Atlantic privies and hygiene as Homewood Museum’s 2021 Pinkard-Bolton intern, questions the assumption that the privy was divided along gender lines. It is possible, she posited, that the privy was used by the Carroll’s enslaved workers on the east side, along with the free white children in their charge, and the free white residents of the house, and their guests, on the west side.

What is more certain, however, is that the enslaved residents at Homewood were tasked with cleaning the privy, even if some enslaved female workers were permitted to use the privy during the course of their child-minding duties. For the Carrolls, the privy was an elegant extravagance; for the enslaved families of African descent at Homewood, it was likely an additional burden.

The 2022 restoration was made possible thanks to generous support from the Baltimore National Heritage Area and the Ensign C. Markland Kelly, Jr. Memorial Foundation. Research on the history of the privy was supported by the Pinkard-Bolton Internship Program, which provides Johns Hopkins undergraduate students with the opportunity to gain significant understanding of the museum profession through work at Homewood Museum.